They are known for their alarm signal: when startled or frightened, a swimming beaver will rapidly dive while forcefully slapping the water with its broad tail, audible over great distances above and below water. This serves as a warning to beavers in the area. Once a beaver has sounded the alarm, nearby beavers dive and may not reemerge for some time. Beavers are slow on land, but are good swimmers that can stay under water for as long as 20 minutes.

Beavers do not hibernate, but store sticks and logs in a pile in their ponds, eating the underbark. Some of the pile is generally above water and accumulates snow in the winter. This insulation of snow often keeps the water from freezing in and around the food pile, providing a location where beavers can breathe when outside their lodge.

The North American beaver's preferred food is the water-lily (Nuphar luteum), which bears a resemblance to a cabbage-stalk, and grows at the bottom of lakes and rivers.[9] Beavers also gnaw the bark of birch, poplar, and willow trees; but during the summer a more varied herbage, with the addition of berries, is consumed. These animals are often trapped for their fur. During the early 19th century, trapping eliminated this animal from large portions of its original range. However, through trap and transfer and habitat conservation it made a nearly complete recovery by the 1940s. Beaver reintroduction in British Columbia was facilitated by Eric Collier as recounted in his book Three Against the Wilderness. Beaver furs were used to make clothing and top-hats. Much of the early exploration of North America was driven by the quest for this animal's fur. Native peoples and early settlers also ate this animal's meat. The current beaver population has been estimated to be 10 to 15 million; one estimate claims that there may at one time have been as many as 90 million.

Beavers fell trees for several reasons. They fell large mature trees, usually in strategic locations, to form the basis of a dam, but European beavers tend to use small diameter (<10 cm) trees for this purpose. Beavers fell small trees, especially young second-growth trees, for food. Broadleaved trees re-grow as a coppice, providing easy-to-reach stems and leaves for food in subsequent years. Ponds created by beavers can also kill some tree species by drowning but this creates standing dead wood, which is very important for a wide range of animals and plants.

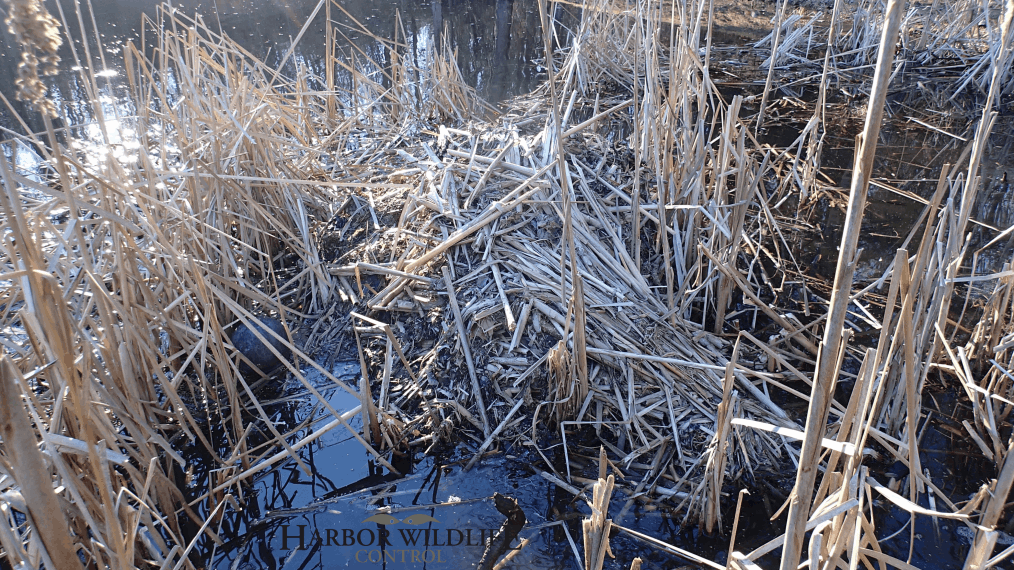

Beaver dams are created as a protection against predators, such as coyotes, wolves and bears, and to provide easy access to food during winter. Beavers always work at night and are prolific builders, carrying mud and stones with their fore-paws and timber between their teeth. Because of this, destroying a beaver dam without removing the beavers is difficult, especially if the dam is downstream of an active lodge. Beavers can rebuild such primary dams overnight, though they may not defend secondary dams as vigorously. (Beavers may create a series of dams along a river.)